(the first in a series of early university papers on ethics, i originally wrote this article in the fall of 1997 to examine the basic morality of abortion)

Abortion is considered a proverbial “black hole†in today’s age of political correctness. politicians do not want to reveal their views on abortion for fear of voter reprisal, and consequently, lawmakers have avoided creating any new legislation regarding the legal status of the fetus. Philippa Foot alludes to this problem of fetal status in her landmark paper “abortion and the doctrine of double effect.†For foot, the bigger question is whether or not it is permissible to act in a particular fashion when the interests of persons are set against each other.

In order to settle this conflict, foot initially proposes a solution used commonly by catholics called “The Doctrine of Double Effect†(DE). Her view is that DE fails when tested by certain philosophical scenarios. consequently, she has developed her own theory by which moral permissibility can be judged. To accomplish this, foot introduces the idea of a conflict between negative and positive duties, the resolution of which will supposedly yield a clear understanding of human moral intuition. Despite its improvement upon DE, foot’s account of moral permissibility fails to consider specific counterexamples which seem to reverse any verdict of moral permissibility as outlined in her original thesis, and therefore leaves her argument open to plausible criticism.

DE lends a great deal to the formation of foot’s argument concerning negative and positive duties. the version of DE most called upon by catholics suggests that “it is sometimes permissible to bring about any oblique intention that one may not directly intend,†(“the problem of abortion and the doctrine of double effect,†virtues and vices and other essays in moral philosophy, (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1978, p20). Thus, the doctrine draws a distinction between those “voluntary†actions which an agent directly intends, and that which the agent foresees as a result of such action. It is possible, in this instance, for the results of an agent’s actions to be regretted but still desired as a necessary means to an end. Foot uses the example of lunatics who are kept in mental hospitals to ensure public safety. Their detention is regrettable, but necessary as a means to keep society safe.

DE lends a great deal to the formation of foot’s argument concerning negative and positive duties. the version of DE most called upon by catholics suggests that “it is sometimes permissible to bring about any oblique intention that one may not directly intend,†(“the problem of abortion and the doctrine of double effect,†virtues and vices and other essays in moral philosophy, (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1978, p20). Thus, the doctrine draws a distinction between those “voluntary†actions which an agent directly intends, and that which the agent foresees as a result of such action. It is possible, in this instance, for the results of an agent’s actions to be regretted but still desired as a necessary means to an end. Foot uses the example of lunatics who are kept in mental hospitals to ensure public safety. Their detention is regrettable, but necessary as a means to keep society safe.

Foot begins to expand DE by using scenarios which seem altogether unrealistic, but are still helpful in evaluating theories of moral permissibility. All decisions regarding the outcomes of these cases are judged by first-order intuition, or more simply, instantaneous deliberation. The scenarios are used to provoke, and consequently identify particular human responses to specific ethical situations in the hopes of gaining insight to the inner workings of the human mind and the genesis of personal morality. It is with this in mind that we now turn to Foot’s example of the “fat man†and his five spelunking friends.

The case is laid out as follows: six friends are cave exploring and they “imprudently†let the fat man lead the excursion. Unfortunately he gets stuck in the mouth of the cave, tail first believe it or not, and traps the rest of his friends inside. A leak in the cave is discovered, endangering the lives of all six explorers, who, in order to save themselves, have the opportunity to use their dynamite to blow open the mouth of the cave. The problem faced by the five is whether or not they may use the dynamite. The problem faced by a philosophy student is whether or not the fat man’s death is a foreseen side-effect of using dynamite.

DE suggests that it is impermissible to use the dynamite because the death of the fat man could not be considered an oblique intention. Using dynamite to open the mouth of the cave is to directly intend the fat man’s death, because it is a certainty that the dynamite will kill the fat man. Foot tells us that “certainties†cannot be used by true moral agents as “possibilities†when the end is guaranteed. If it is known that a fetus will certainly die in an effort to save the mother, then any reference to “probability†in the context of DE is erroneous. Consequently, “probable outcome†cannot be substituted for “certainty†in order to make the decision to kill the fat man more palatable for those involved. So by DE, it is morally impermissible to kill the fat man, despite all our intuitions to the contrary. This is one of the key criticisms that foot uses when developing her duty-based system of judging moral permissibility.

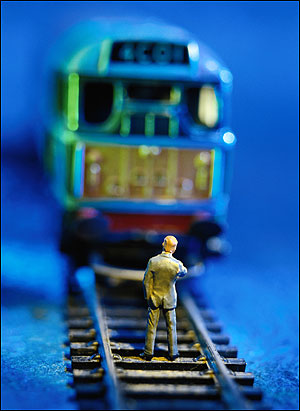

To begin the comparison of her own theory to DE, foot uses the classic case of a runaway trolley, commonly referred to as “the trolley problem.†The driver of this trolley may only steer from his present course onto a supporting track or remain on his present course. five men are working on the track straight ahead, whereas only one man is working on the supporting track to the right. The question posed by this case is whether or not it is morally permissible to steer the train off the main line and kill the one man working on the supporting track. Foot asserts that “it is one thing to steer towards someone foreseeing that you will kill him and another to aim at his death as part of your plan,†(p23). The corollary is that if someone is not killed, the moral agent will not actively pursue and kill any fortunate survivors whose lives were spared under the original circumstances of the case.

In foot’s account, the fact that the trolley is out of control plays a major role in determining the moral permissibility of any action taken by the driver. If the driver does nothing, he is passively allowing the trolley to kill the five people on the track ahead, but if he turns the trolley onto the supporting track, he is actively killing the one person on that track. the question then remains: are we as morally culpable for what we do as for what we allow to be done? Foot insists that the idea of allowing is extremely import when determining the outcome of these cases. “forbearing to prevent†in her account is the duty to intervene in order to protect. This is what foot defines as a positive duty. “consent of action without reproach†is the duty to leave alone and not to bring about undue harm. She calls this a negative duty. These duties together make up the theory which foot uses to judge moral permissibility.

Whenever an ethical situation is presented, positive and negative duties come into conflict, either with themselves, or with each other. Foot insists that there is an absolute way of determining which duty is most important in any given situation, and is therefore the duty which must guide an agent’s actions. In all cases where positive duties are pitted against positive duties, it is the greater positive duty that dictates the course of action. When negative duties are set against one another, it is once again the relative weighing of those negative duties that determines the course of action. Finally, when both positive duties and negative duties are involved, negative duties are always those duties which we intrinsically follow and which allow us to act in the most morally permissible way possible.

It is at this point that foot turns to the problem of abortion, and tries to apply her new ethical tool to analyze three hypothetical situations. In situation one, “nothing that can be done will save the life of the child and the mother, but where the life of the mother can be saved by killing the child,†(ibid. p30). Here, a direct parallel can be drawn to the scenario of the fat man in the cave with his head inside. All will die if nothing is done, but if someone is indirectly killed in an effort to save the rest, it is considered by foot to be morally permissible because it is a conflict of positive duties. Negative duties do not come into play because of the inevitability of harm to all parties if positive duties are not considered. Thus, everyone in the cave will die if an attempt to open up the mouth of the cave is not made, but five will live if it is. Similarly, in situation one of our abortion analysis, the difference between a hysterectomy and directly killing the child, says foot, is minimal. The child must necessarily die in order to save the mother, where the child’s life cannot in any way be salvaged. Therefore, any means by which the death of the fetus is brought about is morally justified. This conclusion goes against DE, but as foot confirms, it reveals why we intuitively feel that killing the fat man would be permissible.

In situation two, the case is set up like this. “it is possible to perform an operation which will save the mother and kill the child or kill the mother and save the child,†(ibid. p30). the only decision to be made in this particular case is whose life will be saved. foot does not come to a precise conclusion about who should be saved, only that it is morally permissible to save someone, rather than seeing all parties perish. consequently, her failure to pursue this line of philosophical inquiry detracts from the credibility of her entire argument. the decision to save either the mother or the child seems to me to be more relevant than establishing whether or not someone should be saved. Granted, her theory explains our moral intuition that saving someone is better than saving no one, but it does not explain why some people place more value on the life of the mother and others place more value on the life of the fetus. This is a direct application of positive duties as explicated in Foot’s thesis, but her theory fails to quantify positive duties when one life is valued against another. It is here that Foot’s argument fails to take flight, and it is for this reason that so many plausible counterexamples have ultimately been found.

Foot suggests that situation three is the most difficult to analyze. In this case, “to save the mother we must kill the child, say by crushing its skull, while if nothing is done the mother will perish but the child can be safely delivered after her death,†(ibid. p31). DE says we may not intervene, since the child’s death would be directly intended, whereas the death of the mother would be classified as an oblique intention. Here DE would insist that it is intuitively wrong to kill one innocent person to save the life of another. Again, the value of each life must be weighed in order to make a definitive judgment about whose life to save. In this case, however, negative duties are set against positive duties, and Foot would have to conclude that it would be morally impermissible to kill the fetus. I think that any universal judgment of moral intuition in this case is impossible, however, because individual views on abortion cannot be explained within Foot’s model. Her theory fails to account for those individuals who, for some reason, see no wrong in killing an innocent fetus to save the life of the mother. I would even venture to say that some mothers would also see no wrong in killing the fetus to preserve their own lives. But Foot avoids any accountability for this omission by assuring us that she is “only trying to discern some of the currents that are pulling us back and forth,†(ibid. p31), and is unable to answer that question herself. She is basically using abortion as a means to clarify the subtle difference between DE and her theory of negative and positive duties.

It is only after examining Foot’s entire argument that we begin to see its inherent flaws. The most basic criticism of her theory is that it is too general, and fails to explain natural human intuitions in several important instances. The first situation involves the fat man in the cave, this time with his head on the outside. In this particular scenario the fat man would not be killed by the flood, so to kill him with the dynamite would be violating a negative duty not to harm him, while providing aid to the spelunkers trapped inside the cave would be a positive duty. As we have established, negative duties always override positive duties in foot’s account of moral permissibility, so to use the dynamite would be impermissible. Intuitively, however, it might seem permissible to save the five by killing the one, and in this case foot’s account does not sympathize with our moral intuitions.

In the second case, a variation on the trolley problem can be found in which the same intuitive disparity occurs. Judith Jarvis Thomson developed a rebuttal to Foot’s theory which is based upon a trolley-passenger, Frank, whose driver informed him that the trolley’s breaks have failed, and who then died instantly of shock. If Frank does nothing in this situation, he is not directly responsible for killing anyone, but five will die as a result. If Frank steers to the right, he will actively be killing one person. By Foot’s account, he would be partaking in an action which is morally impermissible because he is violating a negative duty not to impose harm on the one. Mere intuition suggests that the death of five is far worse than the death of one, if no one person deserves to be spared any more than the others. This example, however, leads us back to the case of the judge who is being implored by a mob to sacrifice an innocent man in order to save potentially countless lives in the ensuing public riot. Here as well, the negative duty not to harm the one scapegoat is overridden by the positive duty to save the five potential deaths caused a riot, or so it would seem. The variables in this parallel are quite similar, and yet the intuitive moral response is quite opposite.

It is with such examples as these that Foot’s argument looses its basic credibility, and students of moral permissibility are forced to look elsewhere for a better explanation of moral intuitions. Foot hints at “involvement in the threat†as being somehow relevant to the case, but she fails to follow this particular avenue of thought, and it is here that her theory fails. “It may also make a difference whether the person about to suffer is one thought of as uninvolved in the threatened disaster, and whether it is his presence that constitutes the threat to others,†(ibid. p29), she insists in a brief sentence at the end of her paper, but she fails to directly incorporate this into her alternative theory to DE.

In this way, the fat man lodged in the cave is considered endogenous to the threat and it is therefore more permissible for his friends to use the dynamite in this case than in the case of a particular judge who was asked to sacrifice an innocent man to an angry mob. If he fails to convict this innocent man for a crime he did not commit, the mob will likely riot, possibly killing many civilians in the process. In this case, the judge is killing an innocent in order to save lives, and so too is frank in our second trolley problem. Why, then, does our moral intuition differ so greatly between the cases? It is precisely this idea of innocence and inalienable human rights that makes killing innocent people who are exogenous to the case impermissible. Once a part of the case, however, their role changes and their protected status as an exogenous entity is replaced by foot’s duty-based theory of moral permissibility. Only then does the sacrifice of an innocent become morally permissible.

Foot’s clearly inconsistent theory of moral permissibility fails to defend itself against the numerous counterexamples which are brought to light by critics. I am not implying that her work is worthless, only that it is a stepping stone to more concrete philosophical theories. It was inevitable that her paper be replaced by more comprehensive works as this area of philosophical inquiry gains insight with each new writer and each new evaluator. Professor Hanna himself drew from the works of Foot and Thomson to arrive at a more comprehensive theory of moral permissibility, and undoubtedly someone will draw from his paper when formulating their own. It is this cycle that will eventually yield what every philosopher of moral intuition has sought: a complete understanding of moral intuitions and their effect on our actions in everyday life.